PocketBook Shop - Buy eReaders, eNotes, eBooks, Audiobooks, and Accessories Online.

Choose your PocketBook

- New

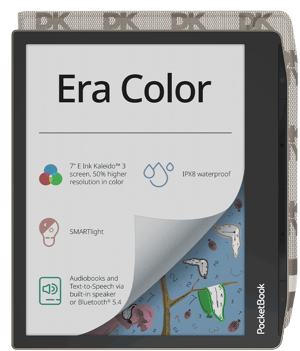

Pre-order. Era Color: fashion edition with Karl Lagerfeld coverproduct_type_E-readersPrice0269,00 €

Pre-order. Era Color: fashion edition with Karl Lagerfeld coverproduct_type_E-readersPrice0269,00 €

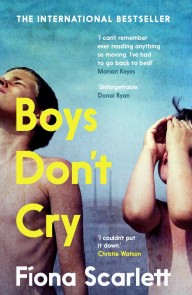

Book of the day

They say boys don't cry.

But Finn's seen his Da do it when he thinks no one's looking, so that's

Price

11,99 €

Price

11,99 €